| Philippines Jewish Community |

|

|

|

The Jewish community of Manila may be the only Jewish community in Asia that has its own locally - slaughtered kosher meat and locally-produced kosher cheese, and it may also be the region's oldest.

The presence of marranos during the country's Spanish colonisation in the 16th century is documented. Two brothers, Jorge and Domingo Rodriquez, who arrived in Manila in the 1590's, were tried in 1593 and convicted of practicing Judaism, along with as many as eight others. And this incident of anti-Semitism is almost unique in the Philippine Jewish community's long and interesting history. The beginning of a visible Jewish community can be pinpointed at 1870, when another group of brothers – the three Levy brothers from Alsace-Lorraine – arrived as refugees from the Franco-Prussian War.  Their first commercial venture was Estrella del Norte – importing Swiss watches. Setting a pattern that would be followed by many other enterprising Jewish immigrants, the Levys diversified into automobiles, perfumes and pharmaceuticals. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 creating a more direct trade route between Asia and Europe, Jews of Egyptian and Turkish origin began to join the small community. The seminal event in Philippine history – the Spanish-American War at the end of the 19th century – was also the seminal event in Manila’s Jewish community. A Syrian-Jewish trader, A.N. Hashim, who had arrived in 1892, helped Filipino patriot Jose Rizal escape from Dapitan. Having recently gained U.S. citizenship, Hashim circulated freely among both Spanish and U.S. forces, providing the latter with intelligence. Â

Although he had landed in Manila with a suitcase of watches, after the war, Hashim took an interest in entertainment, beginning with a bicycle racetrack and later establishing the Manila Grand Opera House. He later diversified into government supply contracting (for both the U.S. and Filipino governments), mining, and import-export. Among the 70,000 United States troops that served in that conflict were a number of American Jews who liked what they found and stayed on at the end of their tours of duty. Notable among them was John M. Switzer, who was a classmate of Herbert Hoover’s at Stanford. Switzer was demobilised in Cebu in 1901, and by 1903 had developed a distribution business in canned goods through small Chinese merchants throughout the far-flung Philippine provinces. It was a business model that proved wildly successful, and brought his company and his leadership to the attention of Pacific Commercial Company, a Jewish-owned conglomerate, which acquired Switzer’s company, and his services as Vice President, in 1911. Meanwhile, Emil Bachrach, a Russian émigré to the U.S. in 1886, read extravagant newspaper accounts of Admiral Dewey’s Manila Bay victory, and decided the Philippines was the answer to his numerous health conditions. He landed with US$1000 in Manila in the early 1900’s, establishing first a furniture company and eventually moving into automobiles. From private cars to taxi services, to provincial bus routes, Bachrach became a Director of the People’s Bank and helped organise the Philippines’ first airline. Bachrach became a major benefactor of the Jewish community, and the community’s second synagogue was named in his honour. While identifying as Jewish, these early community members were not particularly religious. They viewed themselves, and the Filipinos viewed them, as Americans. The first congregation was not established until 1917, and the first synagogue was built in 1924, on land purchased in 1919. Two hundred Jews were members in 1925, with a ratio of about 3:1 of Ashkenazim and Sephardim. Â

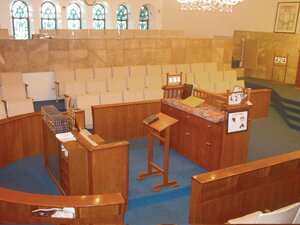

Religious services before 1924 had been haphazard. In 1905, a Mr. Ginsberg of Singapore had donated two Torah scrolls to be held as long as services for the High Holidays and Pesach were conducted. When those services lapsed, in 1909 and 1910, Mr. Ginsberg reclaimed his Torahs. In 1919 a National Jewish Welfare Board was established, and began bringing in kosher food, wine and matzot. As the business community continued to grow, more religious Jews came to Manila. During Hitler’s rise to power, Philippine President Quezon offered to accept up to 10,000 German and Austrian Jewish refugees, partly due to the urging of prominent Manila community members of the time. Paula Brings, who arrived with her physician husband, recalls: “The Jewish community in Vienna had been listing job openings all over the world, and we had seen one for a professor of physics at the University of the Philippines. We applied, but it was too late to allow correspondences to run the normal course. We took a train to Amsterdam; there we borrowed money from a relative to pay landing fees in Australia. The main thing was to get out of Europe. “We looked for work in Australia but it wasn’t easy for a refugee over thirty. We wrote again to the Philippines and in March 1939 the job came through. The university paid for everything, including our passage… We even had enough to help my husband’s brother through medical school in the States and to bring his mother here from Vienna – she barely made it out in time.†During World War II, the Japanese interned American Jews, but Austrian and German Jews, as citizens of Japan’s allies, were mostly left alone. Again Mrs. Brings remembers: “The Japanese didn’t bother us…The American Jewish group was interned…but the rest of us were left to fend for ourselves.†Ernest Simke, who later became Israel’s honorary Consul-General, noted that in Baguio, Jews were indeed interned: “Only a very small group of [Japanese] officers who were trained and educated in Germany were particularly unfriendly, but in no way aggressive. They did intern the Jews living in Baguio, probably because the Japanese commander there had been trained in the Third Reich. I had taken Filipino citizenship before the war and, when I presented my Filipino passport to the Japanese authorities in Bacalod after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, the officer took a long look at me, looked down at my passport, shook his head, sucked in his breath and said: ‘You put chicken in oven, out should come chicken, not fish.’†While most of the community made it through the war, their synagogue did not. Used as an ammunition depot by the Japanese, it was blown up. A new synagogue was completed in 1947. From a high of about 800, the community dwindled in the 1950’s to about 300. The largest segment was still businessmen, with professionals and academics, including many of the remaining European refugees who did not move on to the US.  The government of the Philippines was the only Asian government to vote in favour of Partition of Palestine in 1947, which led to the establishment of the State of Israel, which has been represented officially in Manila since September 1950. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, the neighborhood surrounding the Bachrach Temple began to deteriorate, and Jews moved into the upscale Makati district. A new synagogue opened in downtown Makati in 1982. A nucleus of religious Syrian Jews from New York formed the bulk of subscribing members that helped finance the new building, along with funds realised from renting out the Bachrach Temple to a commercial entity. A rabbi – R. Benjamin Cohn – arrived with his wife in 1987. The synagogue is part of a beautiful complex that also houses a large function room above the synagogue, a spacious kitchen, a library, classrooms and a mikvah. A supplemental school provides for the Jewish education of the community’s children aged 4 and up, with adult classes available as well. A new kindergarten, Ezt HaHaim, recently opened, and a separate school is being built within the synagogue compound. Services follow the Sefardi nusach but with an occasional Ashkenazi “twist.†Usually there is a minyan for services on Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays as well as on Shabbat. A sit-down kiddush luncheon follows services on Shabbat.  About 100 families hold synagogue membership, and it is estimated that there are between 200 and 500 Jews in Manila and the Philippines altogether. In Pampanga (about 3-4 hours’ drive from Manila), there is a Jewish club called “The Bagel Boys.†Â

While the recent political situation in the Philippines has had some recent turbulence, this has not affected the Jewish community, and in spite of the Muslim presence in the southern Philippine province of Mindanao, the community, while careful about security, has not been threatened in any way since the first Gulf War. The current rabbi, Eliyahu Azaria, is a native of Chicago. He and his wife, Miriam, moved to Manila with their two daughters in 2004, following study and rabbinic ordination (Midrash Sephardi) in Jerusalem. An experienced shochet, Rabbi Azaria works with a farm in Batangas to maintain a supply of kosher beef, chicken and veal, and also supervises kosher cheese and milk production. At the moment, there is no separate kosher restaurant, but meals can be arranged at the synagogue complex, and challah and wine are available there for purchase. Prepared kosher airline meals can be arranged at the larger hotels in Makati, and Rabbi Azaria has a list of kosher foods available in local supermarkets. Currently Jews in Manila include business people and diplomatic families. The Asian Development Bank, headquartered in Manila, and foreign embassies add to the mix of long-term and short-term community members. Manila remains a comfortable home for business people who manufacture not just in the Philippines but elsewhere in Asia. While the community has shrunk considerably since the 1950’s, it remains a vibrant, outgoing, friendly and welcoming Jewish community.  Fact Box BETH YAACOV SYNAGOGUE  (Issue May 2006) |