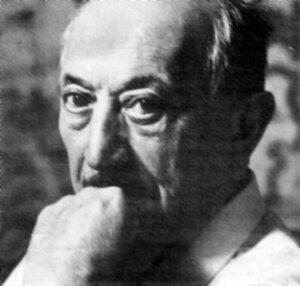

| Simon Wiesenthal (1908- 2005) and his legacy |

|

|

|

It was November of 1979 and I missed my opportunity to interview Simon Wiesenthal in the comfort of my own home. It was not that I was late. He was rather too early for me. I was seven and at the time unable to appreciate the significance of our dinner guest. My parents, Howard & Joan Cohen, were co-chairpersons of the NJ Jewish Federation of Northern Middlesex County's Young Leadership Council. They saved the many letters they received from people touched by the experience of merely hearing him speak in a packed auditorium on November 4, 1979.

Simon Wiesenthal, at the time, was 70 years old and living in Vienna. Despite the flurry of local reporters, to me he was warm and semmingly familiar. I asked if he was an uncle who had come to pay a visit. I was told that he was a Nazi hunter, a survivor and an author. Who I saw did not look like a hunter to me. Simon Wiesenthal was not that sort of man. He sought justice not revenge, something I admittedly have difficulty understanding from time to time given all that he was forced to endure. I climbed the oak bookshelves in our familyroom where Wiesenthal sat just hours before. I reached for the signed copy of Wiesenthal’s book The Murderers Among Us, published in 1967. His book of memoirs was my introduction to the Holocaust. I was to learn that during a visit to promote the book, Wiesenthal found Hermine Ryan, a housewife in Queens, New York who had supervised the killings of several hundred children at Majdanek. She was extradited to Germany for trial as a war criminal in 1973 and received life imprisonment. I later read a copy of his book, The Sunflower- On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness. In this book, Simon Wiesenthal details just one event that occurred while he was a concentration camp prisoner but discloses much about his own remarkable sense of morality, justice and strength of character. He was asked by a dying Nazi for forgiveness. As Wiesenthal recalls, “Well, I kept silent when a young Nazi, on his deathbed, begged me to be his confessor. And later when I met his mother I again kept silent rather than shatter her illusions’s about her son’s inherent goodness…There are many kinds of silence. Indeed it can be more eloquent than words…†He further explains that, “we who suffered in those dreadful days, we who cannot obliterate the hell we endured, are forever being advised to keep silent.† Simon Wiesenthal was anything but silent throughout his life. His actions carried with them the echoes of those “eleven million people†that lost their lives in the death camps. Simon Wiesenthal was born on December 31, 1908, in Buczacz, in what is now the Lvov Oblast section of the Ukraine. In 1936, Simon married Cyla Mueller and worked in an architectural office in Lvov. Their life together was happy until 1939 when the world began to change before their eyes. In a fight for survival, he was able to make a deal with the Polish underground. For supplying them with detailed charts of railroad junction points that he had made, he secured false papers for his wife that allowed her to avoid deportation to the concentration camps. In August 1942, Wiesenthal’s mother was sent to the Belzec death camp. He was arrested and captured but survived forced labour and the death camps. As he describes, in The Sunflower, “Our hunger was almost unbearable: we were given pratically nothing to eat. We threw ourselves on the ground, tore up the scanty grass, and ate it like cattle…The corpses were piled on to the handcarts, which formed and endless procession.†While he and his wife Cyla survived, they together mourned the loss of eighty-nine relatives. Nearly all the members of their families had perished. Wiesenthal was under one hundred pounds and barely alive when Mauthausen was liberated Americans on 5 May 1945. After liberation, Wiesenthal began gathering and preparing evidence on Nazi atrocities for the War Crimes Section of the United States Army for use in the war crime trials. He also worked for the Army’s Office of Strategic Services and Counter-Intelligence Corps and headed the Jewish Central Committee of the United States Zone of Austria, a relief and welfare organisation. In late 1945, he and his wife, whom he believed to be dead, were reunited. In 1946, the couple’s only child, Pauline, was born. In 1947, Wiesenthal and thirty volunteers opened the Jewish Historical Documentation Center in Linz, Austria, for the purpose of assembling evidence for future trials. In 1954, the office in Linz was closed and its files were given to the Yad Vashem Archives in Israel, except for one - the dossier on Adolf Eichmann. Wiesenthal continued to run an occupational training school for Hungarian and other Iron Curtain refugees, but never abandoned his search for Eichmann. Despite popular belief, it is reported that Wiesenthal did not actually hunt for the Nazi’s himself, but rather he worked tirelessly on his fact finding missions utilising every resource available. As expressed best by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, “With an architect’s structural acumen, a Talmudist’s thoroughness, and a brilliant talent for investigative thinking, he pieces together the most obscure, incomplete, and apparently irrelevant and unconnected data to build cases solid enough to stand up in a court of law.†In 1959 Eichmann was at last captured, by Israeli agents, in Buenos Aires. He was brought to Israel for trial, found guilty of mass murder and executed on 31 May 1961. The capture of Eichmann, prompted Wiesenthal to reopen the Jewish Documentation Center, this time in Vienna. He concentrated on the hunting of war criminals and prioritised cases. Karl Silberbauer, the Gestapo officer who arrested Anne Frank, was high on his list, as Dutch neo-Nazi propagandists were attempting to discredit her diary. The truth was revealed to the world when Wiesenthal located Silberbauer, then a police inspector in Austria, in 1963. “Yes,†Silberbauer confessed, “I arrested Anne Frank.†Wiesenthal has been the recipient of countless honours that include decorations from the Austrian and French resistance movements, the Dutch Freedom Medal, the Luxembourg Freedom Medal, the United Nations League for the Help of Refugees Award, the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal and the French Legion of Honor. In November 1977, the Simon Wiesenthal Center was founded and named in his honour. The Center continues to be a drving force behind the fight against bigotry and anti-Semitism worldwide. It is an international center for Holocaust remembrance and the defense of human rights worldwide. As Wiesenthal remarked, “I have received many honours in my lifetime. When I die, these honors will die with me. But the Simon Wiesenthal Center will live on as my legacy.†Wiesenthal died on 20 September 2005 in his home in Vienna. He was 96 years old. He is credited with ferreting out 1,100 Nazi war criminals since World War II. He told the community in New Jersey that night and again to countless others, “When history looks back,†Wiesenthal said, “I want people to know the Nazis weren’t able to kill millions of people and get away with it.†Historical background adapted from information from the Simon Wiesenthal Center.  (Issue December 2007 / January 2008) |