| The Historic Community of Shanghai, China |

|

|

|

The Jewish community of old-Shanghai boasts a rich history made of distinct waves of immigration and a diverse community representing Bag-hdad, India, Russia, London and most of Eastern and Western Europe once it fell to the Germans.

This busy port on the Yangtze River truly made an international name for itself in the nineteenth century as a major port of trade for opium. In the same treaty that ceded Hong Kong to the British, Shanghai, along with four other key ports, was opened to foreign traders as well.

Many people believe that the history of the Jewish Shanghai community began and ended with the Second World War. The vivid images that period conjures up of a noisy and crowded ghetto of Holocaust refugees soon silenced by their mass exodus at the end of the war were neither the beginning nor the end of the history of the Jews in Shanghai.

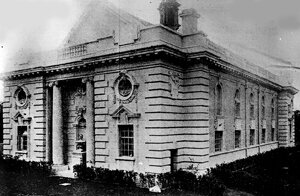

Jews began to settle in Shanghai in the late1840s. The first wave of Jewish settlers was comprised of Sephardic families from Baghdad and Bombay and a direct result of the treaties following the Opium Wars. These early residents were wealthy Jewish merchants and traders. The community’s most prominent families included names such as Sassoon, Hardoon and Kadoorie, names that emerged as community leaders throughout Asia. This was a time of wealth and prosperity for the community and there were many opportunities for new business ventures for the community now comprised mainly of Jews from Baghdad, Cairo and Bombay. They invested, as a whole, in large amounts of real estate throughout Shanghai. It was said by some that Sassoon alone owned 1,900 buildings, rapidly contributing to a change in the landscape of the city and its emergence as a true centre for trade and commerce. The community rented space for worship throughout the 1870s, making a formal organised arrangement in the late 1880s with the consecration of the Beth El Synagogue. Other synagogues followed. In total there were seven synagogues built. In 1898, Shearith Israel Synagogue was established by D.E.J. Abraham. Ohel Moishe Synagogue was founded in 1907 for the Askenazi community. It was also the headquarters of Betat, the Zionist youth movement. In 1904 a prominent community leader, N.E.B. Ezra, founded the community’s first English newspaper - Israel’s Messenger. The Ohel Rachel Synagogue’s sanctuary held up to 700 people and housed thirty Torah scrolls. The site was later home to the Shanghai Jewish School, founded by Horace Kadoorie. These magnificent structures are a testimony to the strength and wealth of Shanghai’s early Jewish community, both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic populations. Four main cemeteries, a hospital and a Jewish club were also products of the rich Jewish life the residents lived.

A second wave of Jewish immigrants began to settle in Shanghai by the 1920s, joining the existing community which was about 1,700 strong. These new immigrants were not merely in search of profitable enterprise and increased trade, they were Russian Jews fleeing the pogroms and restrictive policies from within the Pale of Settlment. Initially they settled mainly in cities along the trans-Siberian rail such as Harbin and Tiajin but the Russian Revolution in 1917 rapidly increased the number of Jews settling in China. They made their way to Shanghai in great numbers by the 1930s, fleeing, this time from the Japanese occupation in Manchuria. The Russians numbered 4,500, substantially growing the Jewish community of Shanghai. They were greatly assisted by a number of charitable institutions established by the older community. Forced to adapt quickly, they became shopkeepers, bakers, and milliners. There are estimates, that at its height, this Russian Jewish community numbered as many as 10,000. They contributed significantly to the plethora of cultural activities available to the Jewish community as a whole. They were of particular influence in fostering the Zionist activism within Shanghai. A number of organisations were the product of this. In 1928, the Russian Jews invited Rabbi Meir Ashkenazi, a member of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement to lead their community. Much loved and respected for his untiring efforts and devotion on behalf of all Shanghai Jewry, Rabbi Ashkenazi led the community until he left China to immigrate to New York in 1949. During World War II, in order to escape the horrors of the Holocasut, Jews sought to find safe havens and routes for escape. Many nations maintained extremely restrictive and rigid immigration policies, apathetic to the plight of the Jews. China, however and specifically Shanghai, opened its doors to refugees seeking merely to survive the horrors of the Holocaust.

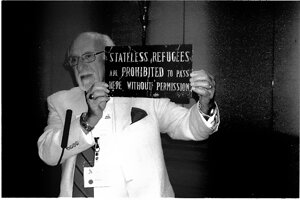

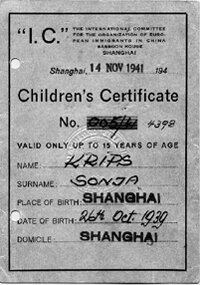

Shanghai sheltered an estimated 24,000 Jewish Holocaust refugees during this time period. There were no passport or visa requirements for entry and it therefore became know as one of the few remaining options for safety during the 1930s and 1940s. Once in Shanghai, the refugees made lives for themselves. They were aided by the permanent Jewish community who quickly mobilised. Following the Japanese invasion of China and occupation of Shanghai in 1937, the Japanese fell under constant pressure, from the Nazis, to promote their anti-Semitic policies in Asia. An official visit by the Gestapo’s Joseph Meisinger as the chief Nazi representative to Japan, was made in China. His plan included rounding up the Jews and sending them off on a ship as prisoners where they would starve to death with no route of escape. Eventually, in 1942, the Japanese devised a plan to appease their German allies, Jewish refugees that had arrived in 1937 and beyond, were eventually required to move within the confines of the Hongkew district ghetto or the “Designated Area for Stateless Refugees.†The Jewish refugees were given one month to relocate into this area. Within Hongkew, Jewish children went to school, played with friends, were on sports teams, went to synagogue, and joined social organisations. Jewish communal life continued to flourish. There were procedures in place to obtain passes to leave the ghetto for a number of reasons including employment. The Shanghai Stateless Refugee Affairs Bureau oversaw the administration of this district.   While undoubtedly, this immigrant population saw its share of hardships while confined to ghetto life, this was war time in an already crowded occupied city. Conditions were extremely crowded in the ghetto and the “Stateless Refugees†were forced to quickly adapt, yet there was a thriving culture of theatre, music, schools, newspapers and cafes. An incredible social welfare system was established through the efforts of Shanghai’s older Jewish community to provide the new refugees with food through soup kitchens and medical care. Only two synagogues still stand and neither is used for its original purpose but they are witnesses to history. The former community, now scattered around the globe, still holds reunions, publishes books and journals, coordinates educational symposiums and produces artwork and poems. China is a permanent part of their psyche.  Photographs contributed by Igud Yotzei Sin and Leah Garrick (Issue November 2007)Â

|

Â