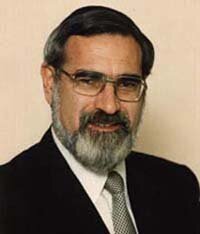

| Chief Rabbi's Rosh Hashanah message |

|

|

|

This past year things have not gone easily for Jews, for Israel or the world. In Britain there has been a continuing campaign of demonisation against Israel. Elsewhere terror and violence have reduced entire countries to what Hobbes called ‘the war of every man against every man’ in which life is ‘nasty, brutish and short’. What is it that we are living through?

The answer is change. Of all things, change – massive, rapid and systemic – is the hardest to live through. We crave the familiar. We need stability. Change is a form of bereavement. We lose the world we once knew. When epoch-making change occurs, there are violent upheavals. It happened in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries after the invention of printing. It happened again in the twentieth century as an after-effect of the industrial revolution. It is happening in our time in the aftermath of globalisation, one of the most profound changes in the history of civilization. Change creates crises of many kinds, but of these, the most important is spiritual. When timeless values are being threatened, do we react by fighting change, if necessary by violence? Do we simply yield to it? Or is there a third possibility? Strangely enough, that is the theme of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The Hebrew word for year, shanah, comes from a root that also means two apparent opposites: ‘to change’ and ‘to repeat’. It embodies the paradox of time. On the one hand there are certain cycles – the seasons, the phases of life – that repeat themselves endlessly. On the other, there is change, sometimes profound and irreversible. We cannot go back to the way things were before computers, mobile phones or nanotechnology. Hence we need the inner resources to deal with the uncertain and the unpredictable. Judaism’s answer is summed up in three words in one of the key prayers on these holy days: teshuvah, tefillah and tzedakah. Teshuvah, penitence, means that in an uncertain world we make mistakes, but we acknowledge them, apologise, set ourselves to do better next time, and move on. Tefillah, prayer, means that we are not alone. God is with us as we journey to our unknown destination. Tzedakah, charity and justice, means that we are there to help those who suffer as a result of change. Some benefit, others lose, and we are commanded to help those who lose. Judaism is our internal compass, showing us the direction even when we lack a map. It is no coincidence that the holiest object in Judaism is a Sefer Torah, something portable. In the tabernacle and Temple, the carrying poles were never removed from the ark, so that the Torah was always ready to accompany the Israelites even if they had to move suddenly. Jews have long known insecurity, and we are prepared for it. For though the world changes, our values do not. Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the two festivals of time itself, are an education in how to face the future without fear. So, whether we face anti-Zionism or wider anti-Semitism or more personal difficulties, it is during these days that we gather the inner strength to do so in the confidence of trust and faith. The values Judaism taught – the sanctity of life, the dignity of the individual and the imperative of peace – remain as compelling today as they did when Moses first communicated them. We are not alone. God is with us. So we travel through the wilderness of time without trepidation, without anxiety, without fear. Our values, our faith, our way of life, do not change. That is why we can cope with change, neither fighting it nor being intimidated by it. This year let us pray with added fervour for peace: for Israel, for our extended family the Jewish people, and for the world. Let us open our hearts to the Divine presence, that we may face the future without fear. May the God of life write you, and Israel, and humankind in the Book of Life.

Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks

|